By Squirrel for Mayor

August 26, 2025

The urban area of the City of Victoria is the Garry oak (Quercus garryana) ecosystem (GOE) – a fact often left out of discussions on the urban forest. GOE or Kwetlal food system in lək̓ʷəŋən language, have been shaped by Indigenous agroecological management for thousands of years. It is dominated by twisted, gnarled Garry oak trees, and includes a mosaic of individual trees, fragmented stands, woodlands, parklands, meadows, grasslands, scattered Douglas-fir stands, and open rocky areas. Garry oak trees can be up to 30 meters tall and are usually in small groups or scattered. The forest understory is composed of shrubs, wildflowers, and other plants. Garry oak ecosystems are among the most endangered ecosystems in Canada with only three percent remaining in a natural state. In Canada, they occur only on southeastern tip of Vancouver Island and adjacent Gulf Islands, plus two isolated groves east of Vancouver.

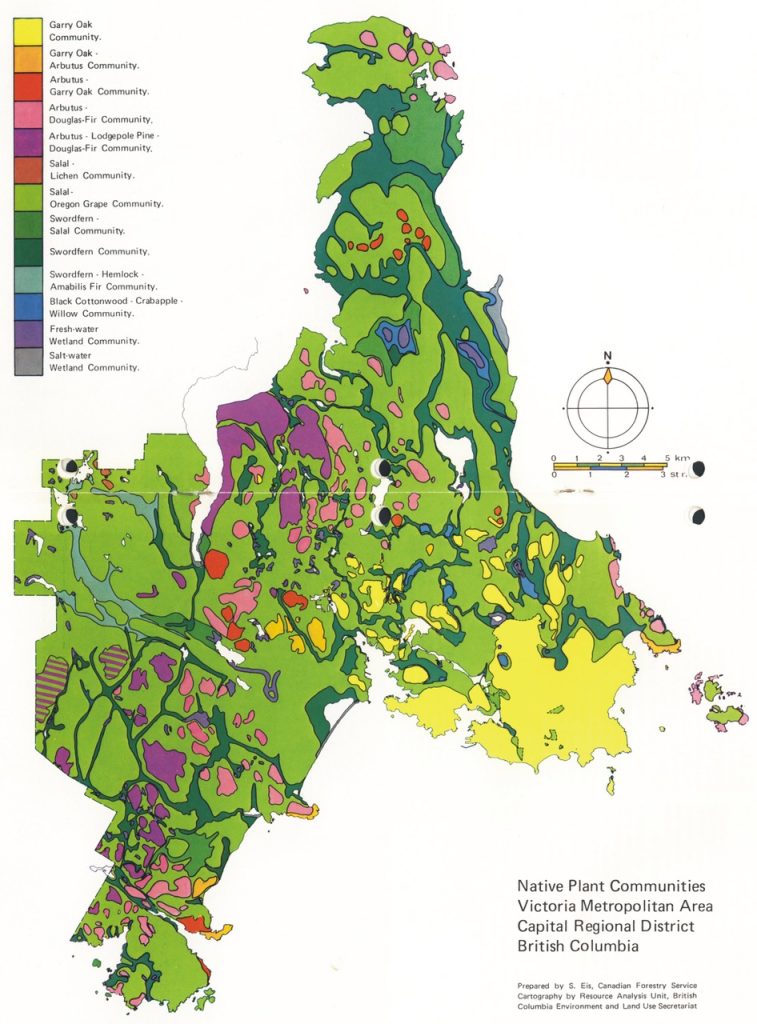

In the Capital Regional District, remnants of the Garry oak ecosystem make up a large part of

the urban forest on the traditional territory of the lək̓ ʷəŋən speaking peoples known today as the Songhees and Xwsepsəm (Kosapsom) First Nations, and the W̱ SÁNEĆ people encompassing the five local communities: BO,ḰE,ĆEN (Pauquachin), MÁLEXEȽ (Malahat), W̱ JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip), W̱ ,SIKEM (Tseycum), and S,ȾAUTW̱ (Tsawout), who have worked on this land since time immemorial and whose historical relationship to the land and territories continues to this day.

Garry oak ecosystems are a subcomponent of the Coastal Douglas-fir ecosystem. Garry oak trees are the only native oak in British Columbia and are found at low elevations in deep meadow soil, and on dry, rocky slopes with shallow soil. Within the Capital Region, some places to find relatively intact Garry oak ecosystems include Regional Parks. However, up to 75% of Garry oak trees and related ecosystems are located on what the municipality refers to as private property and there has been no mapping and analysis of the overall ecosystem and individual old-growth native oak trees on private property in the region in over 20 years, presenting an obstacle to Indigenous stewardship. Many old-growth trees, defined by the Province of BC over 250 years, some exceeding 500 years, continue to thrive in neighbourhoods within the City’s boundaries (Fig. 1).

On August 20, 2025, The City of Victoria hosted an event, Let’s Talk: OCP Update – Public Hearing Information Session about the 10-Year Official Community Plan Update from 12 noon to 1 pm. The OCP charts a course for Victoria to establish goals aligned with community aspirations, regional directions, provincial requirements, and design guidelines for the built environment to guide long term growth. Anyone who signed up for free could join over the Teams meeting platform. Presentation was by Lauren Klose, Senior Planner, Manager of Community Planning, and will be available at engage.victoria.ca/ocp

A total of 62 registrants from across the city logged onto the Teams meeting. The Public Hearing is scheduled for September 11, 2025 at 6:30pm. The core materials Council will consider are now available for public review: engage.victoria.ca/ocp

The meeting underscored the ongoing dialogue surrounding land use and urban trees and their role within the broader ecosystem, highlighting a crucial intersection of environmental stewardship and urban planning for the City of Victoria’s 12 neighbourhoods (Burnside/Gorge, Vic West, Fairfield/Gonzales, Oaklands, Rockland, North Jubilee, South Jubilee, Fernwood, James Bay, North Park, Downtown, Hillside/Quadra).

Intertwined with the early history of settlement, ongoing environmental colonialism led to the destruction of the environment that Indigenous peoples owned (unceded territory), managed, and relied on for survival. Prior to European settlement, most of the land now within the City of Victoria (with the exception of the shorelines and the low-lying riparian areas), supported the Garry oak ecosystem. The open woodland character resulted from millennia of Lekwungen land management and harvesting. In the absence of these activities, the landscape would be dominated by closed stands of Douglas-fir and Grand fir. The Lekwungen people continue to harvest and pitcook wild kwetlal (camas) from the Garry oak community (Fig. 2).

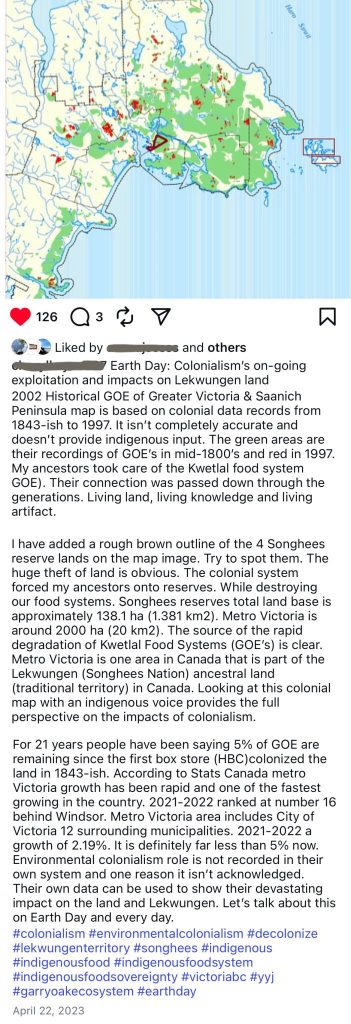

The Greater Victoria region also hosts a high concentration of rare species, and as such, has been identified as a ‘hot spot’ for BC’s biological diversity. Garry oak meadows and associated ecosystems are globally rare and ranked as the most diverse terrestrial ecosystems in British Columbia. Garry oak meadows and associated ecosystems have been observed as being in decline and threatened for over 30 years, and currently, are listed as ‘critically imperilled’ provincially and globally due to ongoing environmental colonialism (Fig. 3). For Earth Day 2023, Cheryl Bryce, Songhees Nation member and knowledge-keeper published an Instagram post about “Colonialism’s on-going exploitation and impacts on Lekwungen land” using a Garry oak map by ecologist,Ted Lea (2006).

Colonial maps have historically erased Indigenous cultures and territories. Historical maps based on colonial data records as well as current mapping projects in the Metro Victoria area are not completely accurate if they do not provide Indigenous input and fail to acknowledge the impacts of environmental colonialism.

Older Garry oak trees and fragments are essential for providing numerous ecosystem services, including habitat and food for a high diversity of soil, plants and animals, especially species at risk. These trees also play a key role in carbon sequestration, helping to fight climate change, and support biodiversity by creating rich, varied ecosystems. Furthermore, they contribute to cultural heritage and can provide opportunities for recreation and education by supporting unique landscapes.

The Coastal Douglas-fir Moist Maritime Biogeoclimatic subzone (CDFmm) is a unique set of associated ecosystems that occurs on a narrow strip of south-east Vancouver Island, portions of the Gulf Islands, and pockets along the south coast and mainland of British Columbia. In this region, in the rain shadow of Vancouver Island and the Olympic Mountains, a Mediterranean-like climate exists, which allows for a rich flora and fauna to thrive. It is important to understand that the Coastal Douglas-fir includes far more than just Douglas-fir forests. In addition to those forests, the zone includes a wide variety of ecosystems, including Garry Oak ecosystems, wetlands, and shorelines. https://www.cdfcp.ca/about-the-cdfcp/

There is 100% unanimous consensus that there is CDFmm habitat in all neighbourhoods across the City of Victoria by the provincial and federal governments, WWF, UNESCO World Heritage, CDF ecosystem experts, and Greater Victoria Naturehood.

Plantable Space

During the online session, a live chat for registrants was monitored by City staff to ask questions in writing. One of the first questions in the chat was about Plantable Space metrics in the Draft OCP document as it relates to the urban forest:

“There is a focus on climate action and resilience through emissions reductions and density, along with details on design guidelines and built forms. Can you identify the percentage of plantable space? Plantable space is a leading metric, while canopy cover is a lagging indicator of a healthy urban forest. For example, MMH is 6.5% (a variance like open site space, and not legislated).”

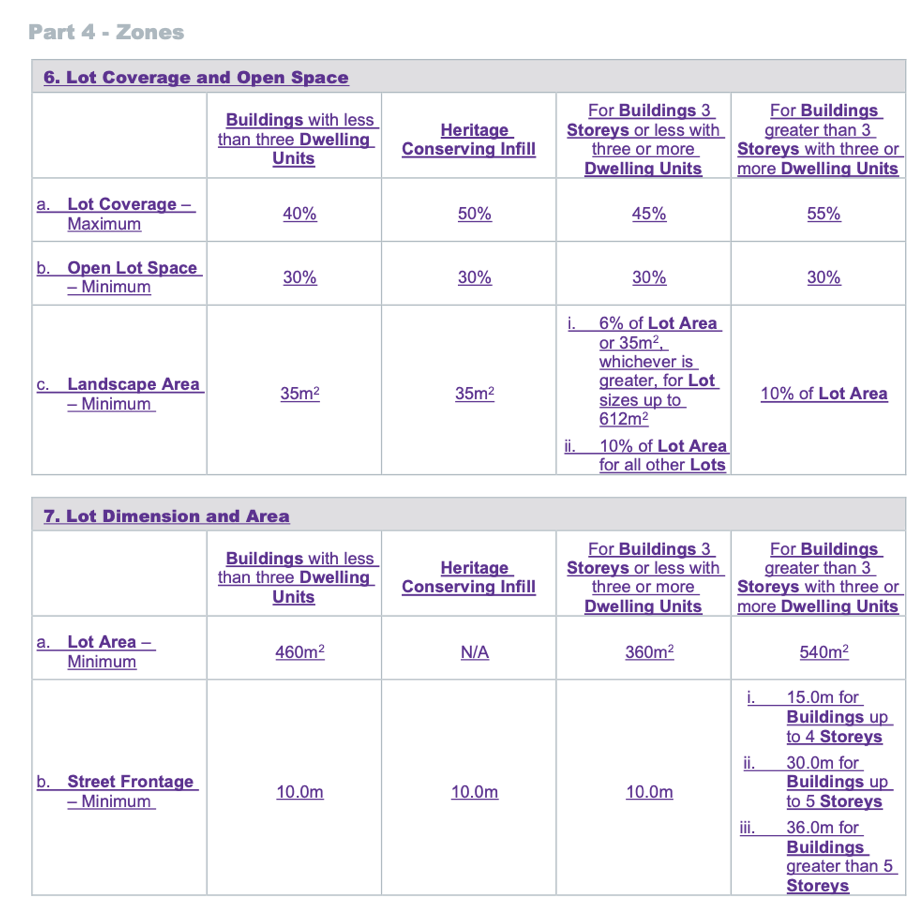

The question about plantable space in the chat room was in reference to Landscape Area minimums under 4.1 General Residential District – 1 Zone (GRD-1), Part 4 – Zones, 6. Lot Coverage and Open Lot Space in The Zoning Bylaw 2018 Bylaw Amendment (Blackline Copy – July 2025). The Landscape Area minimum is 6% for buildings with less than: three Dwelling Units; Heritage Conserving Infill; 3 Storeys or less with three or more units the building. 10% for Buildings greater than three Storeys (up to 18 Storeys) shown in Fig. 4.

It triggered some great questions about the urban forest and gave a glimpse into how some attendees who are members of a BC Elections local third party advertising sponsor, view urban forests, the built environment, and climate resilience.

One attendee responded to the question about plantable space:

“Urban trees are houseplants. If you want to protect forests you need to discourage the sprawl we are seeing way outside of Victoria. The best thing Victoria can do is densify” (Fig. 5).

The Inconvenient Garry Oak Ecosystem

The concept of urban trees as “houseplants” may resonate with some, suggesting that urban trees, much like indoor plants, require care and attention within their specific environments. Houseplants can improve the air quality of a room in sufficient numbers, but are often non-native and selected for aesthetic appeal. Native trees, on the other hand, thrive in local environments, provide habitat for wildlife, support local ecosystems, and require less water and maintenance once established.

However, reducing the significance of the urban forest in this region to “houseplants” arguably erases the history of the Garry oak ecosystem (GOE), which emerged after the glacial retreat around 10,000 years ago and is considered a “living artifact” by the Lekwungen people.

Indigenous scholar Billy-Ray Belcourt argues in the journal article, “Animal Bodies, Colonial Subjects: (Re) Locating Animality in Decolonial Thought” how animal domestication, speciesism and other modern human-animal interactions in North America are possible because of and through the erasure of Indigenous bodies and the emptying of Indigenous lands for settler-colonial expansion.

In Part 1 of the Draft OCP: Truth and Reconciliation – Vision 2050 Reconciliation Actions (pg 17-18) there are several objectives listed to adhere to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP ) to achieve meaningful reconciliation in land use decisions. Including, “to understand the practices that contributed to ecosystem conservation over millennia and collaboratively identify opportunities to braid Indigenous knowledge systems with Western science in the preservation and enhancement.” This sounds great, but reconciliation cannot occur through performative actions like supporting conservation and ecosystem values in one document, while not providing the mapping and analysis, legislation, zoning bylaws, and design guidelines to achieve it in another.

This leads to questions such as: How does settler colonialism’s representation of erased landscapes invite people to ignore the presence of this unique and rare ecosystem and, in a way, legitimize the further destruction of its existence? How can acknowledging the existence of Garry oaks and 1,645 other co-evolved species including 694 species of plants, seven reptile species, seven amphibian species, 104 birds and 33 mammals living on private property assist with its survival?

Ecosystem denial is not confined to comparing urban trees with houseplants.

On February 27, 2025, a Reddit/VictoriaBC commenter became unsettled and accused a defender of the Garry oak ecosystem of leveraging it as a “as a cudgel against development” (Fig. 6).

This viewpoint was again activated by the urbanists who spoke at the Special Council Meeting at the District of Saanich’s July 7th meeting regarding the proposed Quadra McKenzie Plan (QMP).

“Building housing inside the city means we don’t have to cut down the forest outside of it, or pave over agricultural land in order to house people. And I personally care more about the forest than the trees I can see from my window. Yes, they are nice but they’re not nearly as important as those forests in fighting climate change or making the local environment better.”

Forests are under duress both in and out of the City limits. Forests on Vancouver Island are either owned by the province for resource extraction, timber or as a recreational forest in a hybrid state managed for extraction. In 2021, the B.C. government shared mapping that identified 2.6 million hectares of old-growth forests considered most at-risk that had been recommended for logging deferrals. More than half of these areas, however, remain open to logging.

Significantly, there no meaningful data to show that sprawl at the interface of wildlands is slowed by development in the City of Victoria. Suggesting that there is a correlation between the two, is purely theoretical and the evidence is not there to support it. People who want to live in rural environments will not be swayed by urban living, and it would also be difficult to measure. We can measure one community, but to suggest it is making a factual difference in another one is irresponsible to imply.

Landscape Area

Landscape Area (space) in the City of Victoria Design Guidelines for housing, typically refers to the total area on a site that is dedicated to natural or green features, which may include lawns, gardens, trees, and permeable surfaces like permeable pavers. This is not, however, the same as Plantable Area (space).

A City representative confirms by email on August 20, 2025:

“They are related but not identical,

Landscape space typically refers to the total area on a site that is dedicated to natural or green features, which may include lawns, gardens, trees, and permeable surfaces.

Plantable space is a subset of landscape space and refers specifically to areas where vegetation can be planted and sustained—usually soil-based and not paved or covered.

The updated zoning bylaws aim to clarify and simplify these definitions, emphasizing the importance of tree retention and planting as part of climate resilience goals. Under the proposed Zoning Modernization, most zones are expected to require a minimum of 6% landscape space. This is part of the broader effort to ensure:

- Tree canopy growth

- Stormwater management

- Improved livability and biodiversity

Some zones may have higher requirements depending on their location, heritage context, or ecological sensitivity.”

Landscape Area and Plantable Space

It not clear what the measurement is for plantable space in the Draft OCP or if they have made changes to the definition.

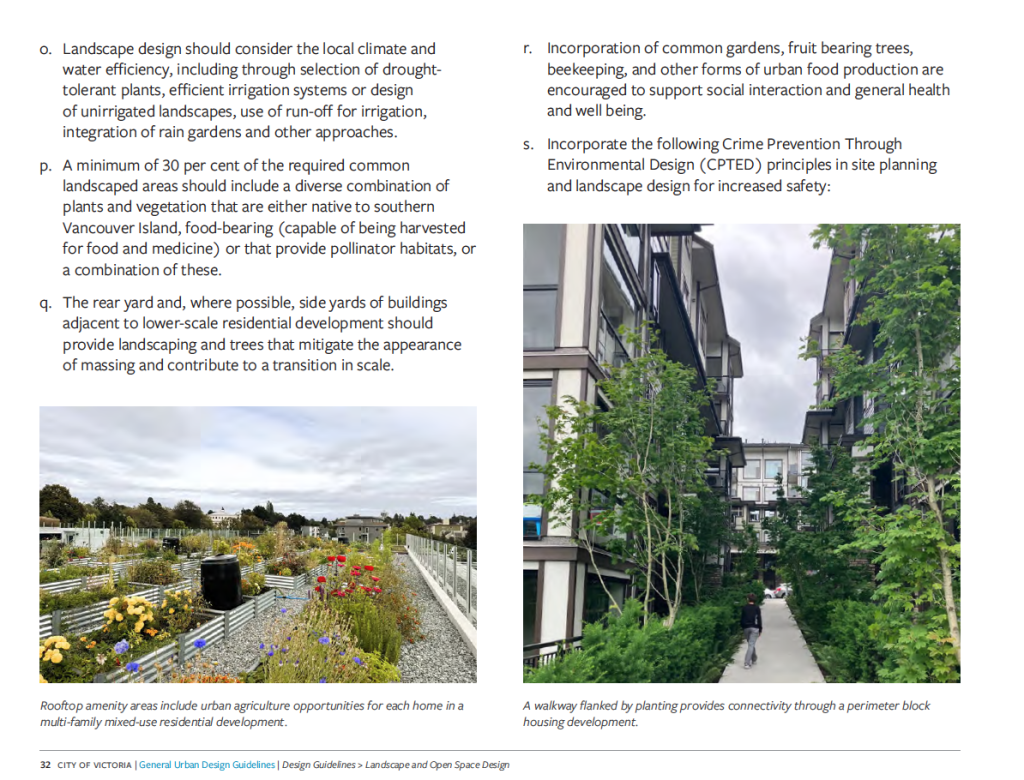

Attachment A1 – General Urban Design Guidelines (OCP Schedule 2A) Summary Victoria 2025, 2.4 Landscape and Open Space Design, Section p., page 32 mentions plants and vegetation.

It reads:

“A minimum of 30 per cent of the required common landscaped areas should include a diverse combination of plants and vegetation that are either native to southern Vancouver Island, food-bearing (capable of being harvested for food and medicine) or that provide pollinator habitats, or a combination of these” (Fig. 7).

City staff confirmed that “under the proposed Zoning Modernization, most zones are expected to require a minimum of 6% landscape space (area).”

What is the difference between plantable space and landscape area? Or what makes plantable space a “subset” of landscape area? And since all buildings in the City of Victoria are zoned for four storey building forms (up to 18 storeys in new Town Centres), these definitions matter.

Please watch this space for updates.

Design Guidelines

You will recall that plantable space is defined in the Missing Middle Housing (MMH) Design Guidelines subject to Schedule P – Missing Middle Regulations (Amended December 7, 2023 Bylaw 23-099). Section 3.4 (definitions linked here): Plantable Area (a single space) is 6.5% of contiguous permeable space to plant a tree. Open site space, also called Landscape Area (space) includes permeable pavers, decks, and other built forms. Site coverage is the building footprint.

Both Open site space and plantable space (a single space) are variances and not legislated. MMH projects, also known now as Delegated Development Permits (DDPs) can have impermeable surfaces on up to 93.5% of their lot. But developers can also choose to pay into a cash-in-lieu fund. Cash-in-lieu charges are for each tree that does not meet the required minimum on a property at a 1:1 ratio. This approach differs from the 3:1 tree retention credit ratio that encourages the preservation of large, healthy specimen trees. It’s important to note that trees retained and replacements made to meet the minimum requirements are exempt from these cash-in-lieu charges. The cash-in-lieu fee is currently $2,000 per tree that falls short of the required minimum, and has proven not be a strong enough incentive for developers to comply with the Tree Protection Bylaw (21-035). Over the past three years, the City has collected $1,047,000 from developments that fell short of the tree minimum, resulting in a net loss of 523 trees from private properties.

Figure 8 shows an example of a MMH (DDP) project in the City of Victoria’s Fairfield Neighbourhood, where the developer paid cash-in-lieu instead of planting replacement trees due to a lack of plantable space. The idea behind cash-in-lieu is that the number of trees removed from private property will be planted on public property. The cost of planting trees in boulevards is at least $1,250 each, and in areas with hardscaping, like Linear Parks proposed in the Draft OCP, the cost rises to $10,000 or more, not to mention the ongoing maintenance required. Many municipalities still use outdated cash-in-lieu fees that don’t reflect the actual costs of planting trees on public land, leading them to operate at a loss.

Neighbourhood Level Tree Canopy Loss and Heat Domes

Returning to the importance of urban trees at the neighbourhood level, a commentary by two members of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment and an organizer with Sierra Club B.C. wrote to the Times Colonist (“Without more trees”). Dr. Bethany Ricker, David Quigg, and Dr. Melissa Lem pointed out in their op-ed the reality of extreme weather events despite advancements in building codes, as well as the now depleted funds to provide vulnerable households with air conditioning units. They caution our government over rapid urban tree canopy loss, reminding readers how the 2021 heat dome claimed the lives of more than 600 people, many of whom died alone in overheated homes.

Their letter continues:

“Our communities are rapidly losing tree canopy, green space and permeable surfaces — the very elements that keep cities cooler during extreme heat.

The 2022 Extreme Heat Death Review Panel is rather unequivocal: A number of deaths occurred in neighbourhoods with large roads, large buildings, high density and low greenness.

It also warned that “declining tree canopy and permeable surfaces in urban areas will increase vulnerability to extreme heat.

Ensuring equitable access to shade, green space and cooling through targeted tree planting and preservation efforts isn’t just about beautifying neighbourhoods — it’s a public health imperative.”

Research indeed supports how deficiencies in tree canopy at the neighborhood-level:

a) diminish residents’ physical and mental health outcomes;

b) removes wildlife habitat and reduce overall species diversity; and

c) reduces ecosystem services capacity, for example, provision of surface shading during heatwaves and reducing peak stormwater flows.

Tree Protection Bylaw and LiDAR

Unfortunately, the Tree Protection Bylaw (21-035) has not been updated since the introduction of the City of Victoria Missing Middle Housing Initiative and the Province of BC Bills 44 and 37, or the City of Victoria Draft OCP. This is significant, because housing policies which prioritize the built environment can undermine physical protections for trees and tree minimums through developments established in the Tree Protection Bylaw – and the families of the wildlife that trees support.

On July 12, 2025, City of Victoria Councillor Dave Thompson wrote a letter in response to “Without more trees” to the Times Colonist highlighting the latest canopy cover metric for the city (Fig. 9):

“Between 2013 and 2023, our urban tree canopy grew by the equivalent of 100 soccer fields, while we added more than 8,000 net new homes (almost entirely multifamily buildings).”

Councillor Thompson’s statement has known limitations. Terra Remote Sensing provided comment on the 2013-2019 City of Victoria change detection analysis, and it is relevant to reflect as the rate of growth drops by 50%. In four short years we are 23 hectares short of the previous four years’ urban tree canopy growth rate. The urban forest net gain was +47.4 hectares between 2013-2019 (+2.37% to 28.83% city-wide), and according to the City’s website an additional net gain occurred in 2019-2023 of +24 hectares (1.26% to 30% city-wide).

The numbers look a lot better over 2013-2023 than 2019-2023. We can see the momentum of canopy growth vs. canopy loss is shrinking fast, and we could soon revisit the 2007-2013 period which produced a net gain of .05% (1 hectare). Canopy goals should be achievable, but you cannot reach a 40% canopy cover target (recommended in the Urban Forest Master Plan 2012 and City of Victoria Draft OCP) if the rate continues to slow and we approach 0% or a net loss scenario. Hence, the question about plantable space.

Billion-dollar real estate industry

At a workshop presented by the Coastal Douglas-fir Conservation Partnership earlier in February 2025, Adam Olsen, former Member of the Legislative Assembly for Saanich North and the Islands and member of the W̱JOȽEȽP Nation and W̱SÁNEĆ people spoke to attendees. His presentation discussed the concept of land ownership, and how “every inch of the territory is touched by the multi-billion-dollar real estate industry” and that “the terrestrial ecosystems such as the Coastal Douglas fir, the Garry oak and the Cedar have been plundered and transformed by urbanization”. Olsen said the focus of the current provincial government “is less on conservation and much more on ramping up resource development” to create more supply of land.

Olsen was more explicit about the economics around private land development and the idea that creating more supply of land by fracking it produces affordability. “It’s a fallacy. It produces more modified units of economic housing to sell and it requires people to be more generous than they’ve proven to be in order for there to be actual affordability to be achieved.” Certainly, the politics of colonial nation-building continues to prove it is less than generous.

Conclusion

The Garry oaks ecosystem persists in every neighbourhood in the City of Victoria; it is an inconvenient fact for civic leaders faced with increasing pressures for land use development within the city.

Garry oak and associated ecosystems in this region have a unique local genetic adaptation would be difficult to re- introduce if lost.

It is essential for our municipal leaders to recognize that the housing legislation in British Columbia and Victoria’s Draft Official Community Plan (OCP) will significantly affect cultural connections to the territory, and green corridors that serve both people and wildlife. Although Bill 44 and Victoria’s Draft OCP do not eliminate local environmental protections such as tree protection bylaws, the new regulations stipulate that municipal guidelines cannot “unduly restrict” density. Tree protection bylaws are rendered moot if the trees fall within a building envelope.

The Draft OCP is not clear about the minimum plantable space required for new developments (stay tuned for an update on this).

British Columbia currently lacks legislation to protect urban forests, and local politicians are responsible for acknowledging the limitations of metrics that measure it. B.C.’s housing strategy makes no mention of trees, greenspace, or urban cooling, and support from local politicians is a crucial step in incorporating tree canopy and climate goals as a core part of B.C.’s housing strategy for a climate-ready future.

Current provincial and municipal legislation has proven inadequate in halting the decline of Garry oaks and other mature trees, particularly given that over 75% of the urban forest is situated on private property. There has been no mapping and analysis of the overall ecosystem and individual old-growth native oak trees on private property in the region in over 20 years, presenting an obstacle to Indigenous stewardship. The City of Victoria Draft OCP only references relatively “intact” Garry oak ecosystems that exist in public spaces and Regional Parks like Mee-qan (Beacon Hill Park).

Overall, environmental colonialism, and urban development has had a major impact on the Lekwungen territory. Plantable space is an important metric for the future of Indigenous stewardship, the survival of Garry oak ecosystem, and for adherence to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP ) to achieve meaningful reconciliation in land use decisions.

The Draft OCP Public Hearing is set for September 11, 2025 at 6:30 pm. You can attend in person, write a letter, call in by phone, or submit a video.

Resources

Acker, Maleea. Gardens Aflame: Garry Oak Meadows of BC’s South Coast. New Star Books. 2012.

Belcourt, Billy Ray. “Animal Bodies, Colonial Subjects: (Re)Locating Animality in Decolonial Thought.” Societies 5.1 (2015): 1-11. Web.

Bryce, Cheryl. “Meegan. Online On Land.” Open Space. 2019 https://vimeo.com/405250132. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Bryce, Cheryl. Earth Day: Colonialism’s ongoing exploitation. Instagram. April 22, 2023.

“Capital Regional District. Garry Oak Ecosystem Information Sheet.” https://www.crd.ca/media/file/may19-2021-ecosysteminfosheets-garryoak. Accessed August 18, 2023.

City of Victoria. Official Community Plan. https://engage.victoria.ca/ocp

City of Victoria. Tree Protection Bylaw.” https://www.victoria.ca/parks-recreation/trees-urban-forest/tree-protection-bylaw. Accessed August 15, 2023

“City of Victoria. Urban Forest Master Plan (2013).” https://www.victoria.ca/media/file/urban-forest-master-planpdf. Accessed 15 August 2022.

City of Victoria, Tree Protection Bylaw (21-035) https://www.victoria.ca/media/file/tree-protection-bylaw-21-035

Coastal Douglas Fir Conservation https://www.cdfcp.ca/about-the-cdfcp/

Lea, Ted. (2006). Historical Garry oak ecosystems of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, pre-

European contact to the present. Davidsonia. 17. 34-50.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285313724_Historical_Garry_oak_ecosystems

of_Vancouver_Island_British_Columbia_pre-European_contact_to_the_present. Accessed

January 25, 2024

Times Colonist. Comment Section, July 02, 2025 https://www.timescolonist.com/opinion/comment-without-more-trees-bcs-next-heat-dome-could-be-even-deadlier-10888783

Times Colonist. Comment Section, July 12, 2025.

https://www.timescolonist.com/opinion/letters-july-12-difference-between-housing-and-shelter-replace-fireworks-10934242#google_vignette

Wilderness Committee. ” “BC government mismanagement of bears a systemic issue”

https://www.wildernesscommittee.org/news/bc-government-mismanagement-bears-systemic-issue