Category: Articles, Letters, and Petitions

-

Setbacks, Soil, and Survival: Why Urban Forest Protection in Victoria Starts with Space

Setbacks are often treated as a technical zoning detail—numbers on a site plan to be minimized in the pursuit of density. In reality, setbacks are one of the most powerful tools a city has to protect its urban forest, safeguard biodiversity, and uphold climate resilience and public safety. In the City of Victoria, where the Read more

-

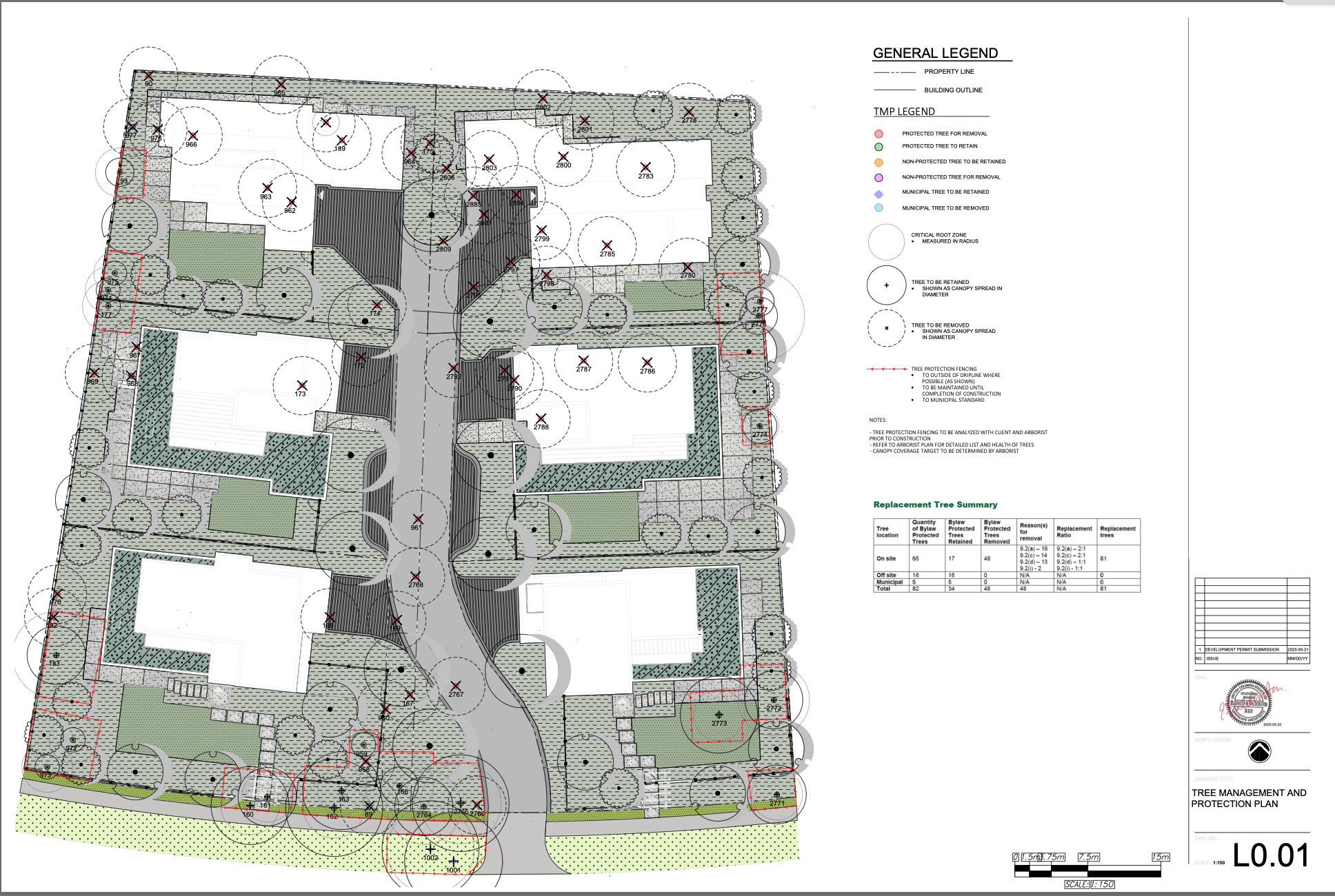

Will Oak Bay Council Allow 48 Bylaw Protected Trees to be Cut for Townhomes in the Uplands? Residents Urge Council to Reject Proposed Development.

2830/2850 Lansdowne Road This proposed development involves two adjacent lots in the Uplands on Lansdowne Road, located on the north side between Ripon Road and Norfolk Road. Both properties are zoned R-2 Residential Use. The purpose of the application is to permit the proposed construction of a Small Scale Multi Unit Housing development consisting of Read more

-

The Inconvenient Garry Oak Ecosystem: Distinguishing Native Trees from House Plants through Victoria’s Draft OCP.

By Squirrel for Mayor August 26, 2025 The urban area of the City of Victoria is the Garry oak (Quercus garryana) ecosystem (GOE) – a fact often left out of discussions on the urban forest. GOE or Kwetlal food system in lək̓ʷəŋən language, have been shaped by Indigenous agroecological management for thousands of years. It Read more

-

Do Tree Protection Bylaws really “protect” the urban forest since the introduction of new housing regulations and legislation?

Tree Protection bylaws for the urban forest are municipal. Each municipality is slightly different, but they are all affected by provincial legislation. Citizens believe that these bylaws protect the urban forest. The word “protection” is in the name, so it’s a fair assumption, but it requires a deeper look. Let’s use the City of Victoria’s Read more

-

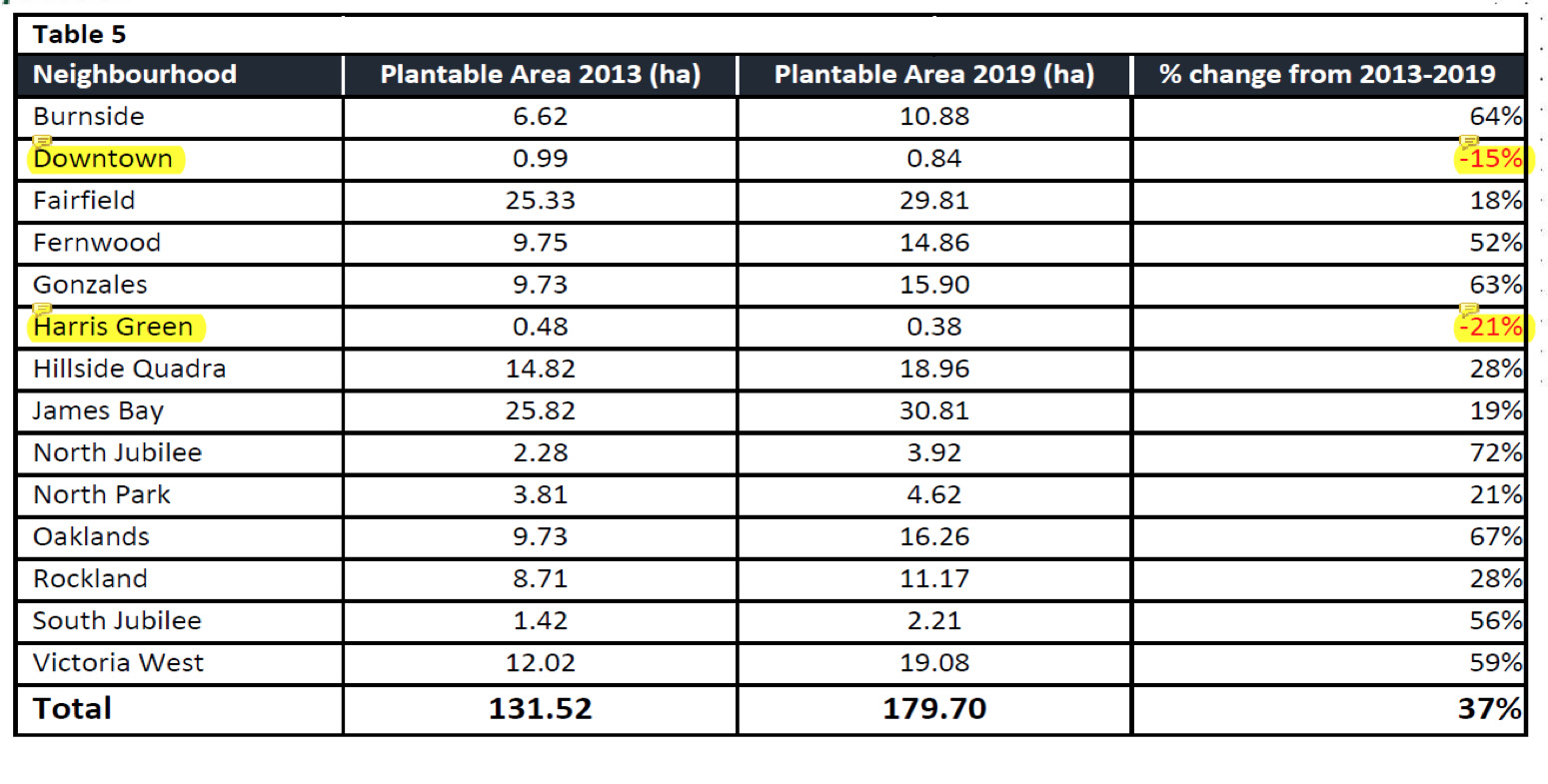

Why is Plantable Space an important metric

As a measurement, plantable space is the leading indicator of an sustainable urban forest, while overall tree canopy measurement is a lagging indicator. A loss of plantable space reduces the opportunity for canopy at the local level, meaning at the neighbourhood level. The benefits that the trees provide and protects the whole of a city for shade, stormwater and heat reduction through evaporation. Read more

-

Index of documentation related to Centennial Square and the Sequoia

Originally posted at CRD WATCH In order to make information about Centennial Square and the Sequoia organized and easily accessible, CRDWatch.ca has made an index of documentation regarding Centennial Square and the Sequoia. The index is a stark challenge to the City of Victoria’s faulty narrative regarding the tree, which collapsed when faced with the analysis of a Read more