Category: News Stories

-

Panama Flats: When Biodiversity and Dog Access Collide — and What Council Decided

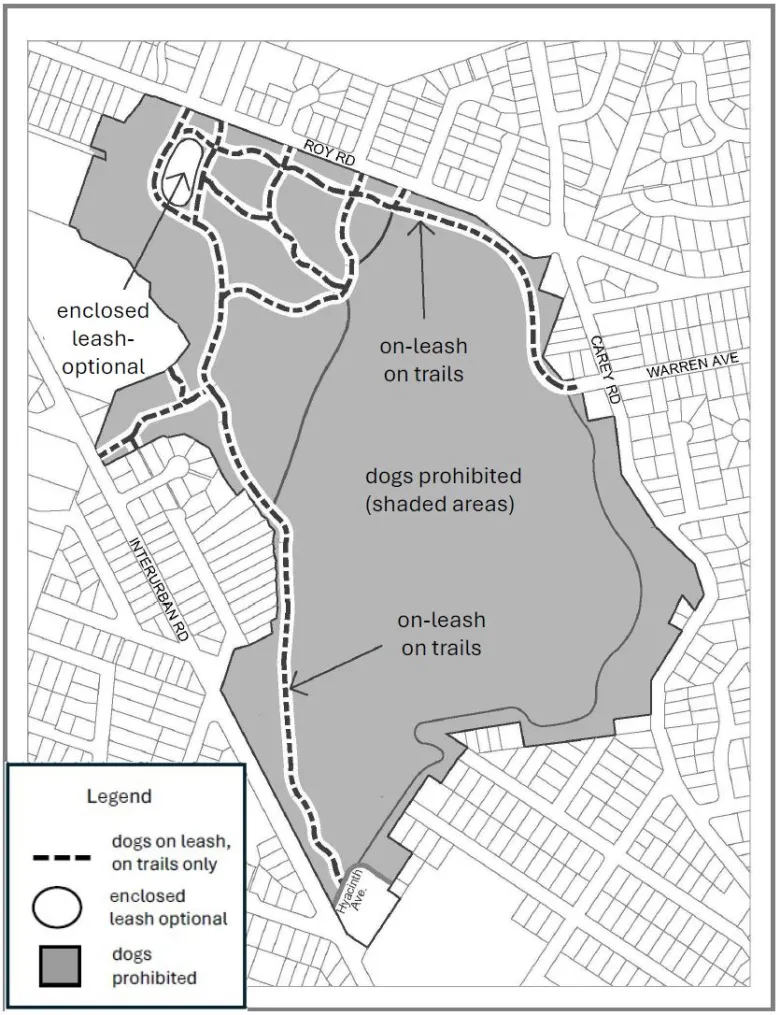

Panama Flats—a 26-hectare wetland and meadow system in Saanich between Interurban and Carey—has been at the centre of a region-wide conversation about how we share urban nature. On January 12, Saanich Council made an important move by rezoning the Flats as a bird and nature sanctuary, formally recognizing one of the region’s most significant urban wildlife Read more

-

Oak Bay – Carrick Trail trail saved: ‘When neighbours come together, good things happen’

Read more at: https://vicnews.com/2025/10/29/oak-bay-trail-saved-when-neighbours-come-together-good-things-happen/ When the District of Oak Bay proposed to put a 15-foot-wide paved bike path over a small natural corridor back in 2024, a group in the community spoke out. Soon, these members banded together to not only protect that little corridor that had come to mean so much to them – they Read more

-

Saanich – Parts of Panama Flats to be designated as park to protect birds, off-limits for dogs

Times Colonist, October 22, 2025 by Michael John Lo Starting next year, staff is set to begin updating trails, fencing and signage in the area to create a dedicated area for migratory birds, waterfowl and rare plants.z Large parts of Panama Flats will eventually become off-limits to dogs, after Saanich council agreed to designate the Read more

-

First Nations-led rally at B.C. Legislature opposes $162 million highway expansion threatening Goldstream River – SELE₭TEȽ.

………………………….. Save Selektl Listen to the videos. Join Carl Olsen and friends @ 10:00 am every Tuesday on the side of the highway infront of Goldstream Park! Write a letter to Premier Eby enough is enough. Do not cut down 700 trees to add barrier to highway. Instead change the speed limit here. How about Read more

-

Neighbourhood saves a tree in Saanich

Times Colonist, Opinion. Letters July 30, 2025 At 5032 Wesley Rd. in Saanich stands an iconic, 100-year-old big leaf maple. Neighbours were surprised when a notice was hammered into the trunk of this tree by Saanich advising that within 10 days, the tree would be cut down to facilitate a developer’s connection to underground sewer Read more

-

Comment: Without more trees, B.C.’s next heat dome could be even deadlier

Re: “Without more trees, B.C.’s next heat dome could be even deadlier,” comment, July 2. Many thanks to Dr. Bethany Ricker, David Quigg, and Dr. Melissa Lem for pointing out in their op-ed the reality of extreme weather events despite advancements in building codes, as well as the now depleted funds to provide vulnerable households with Read more

-

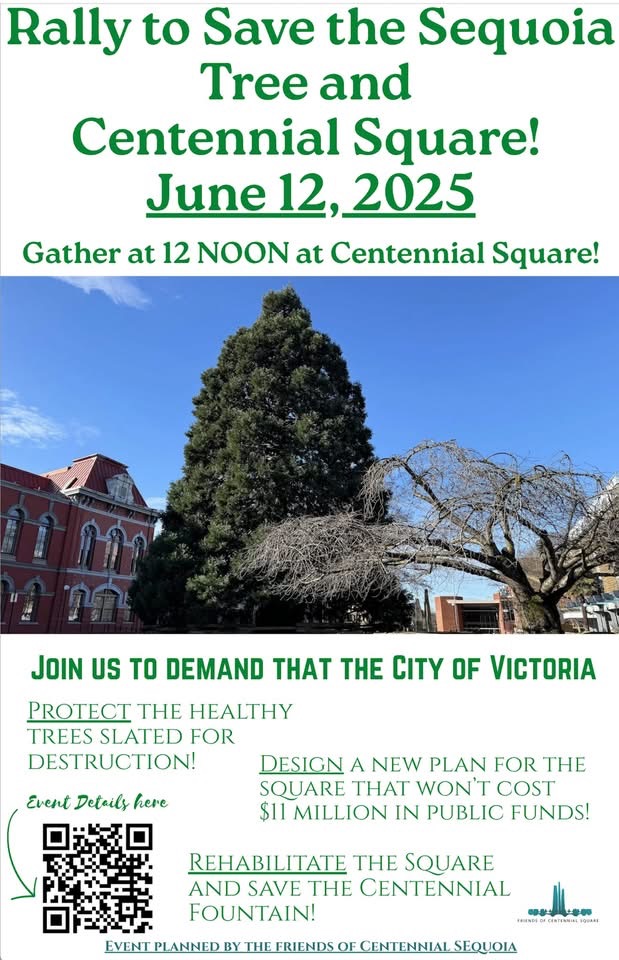

A Rally to Save the Centennial Sequoia. June 12th at 12 noon (lunchtime rally) at Centennial Square, City of Victoria Municipal Hall

The inaugural event attended by Squirrel for Mayor was at “A Rally to Save the Centennial Sequoia,” planned by “Friends of Centennial Square,” a group of residents from the City of Victoria. The rally was aimed at protesting the City Council’s decision to remove a mature sequoia tree to facilitate a redesign of the square. Over time, the Sequoia Read more

-

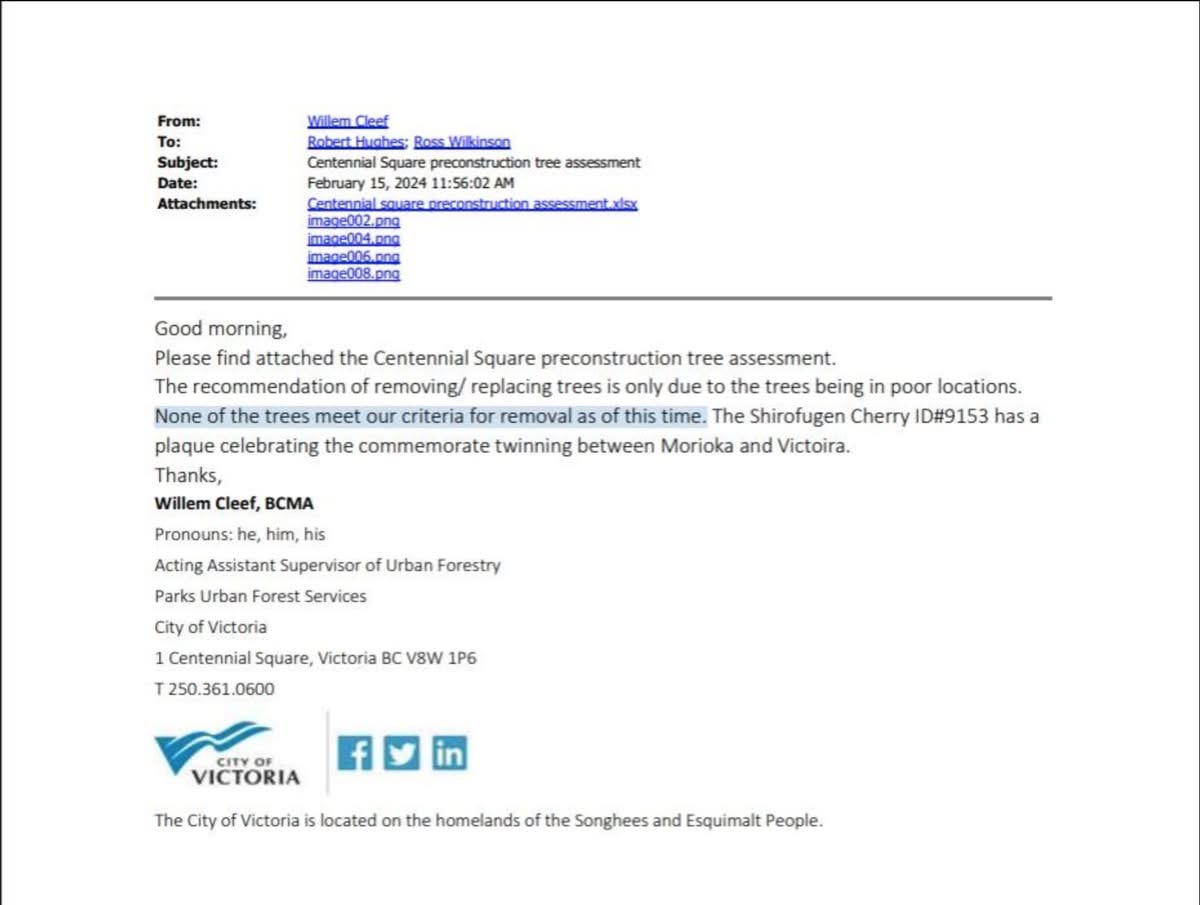

A Freedom of Information response revealed that City of Victoria staff stated in February 2024 that none of the trees in Centennial Square met the criteria for removal.

Originally posted at CRD WATCH A Freedom of Information response revealed that City of Victoria staff stated in February 2024 that none of the trees in Centennial Square met the criteria for removal.The document provides compelling evidence that counters later claims by City of Victoria councillors that the trees are unsafe. The document also underscores Read more

-

Climate funding Victoria’s Centennial Square and the Sequoia tree.

At the January 23rd Council of the Whole Meeting, Councillor Matt Dell shared his experiences of tree removal and replacement regarding the need to advance a city, thus emphasizing the need for context in urban planning. “I grew up in a farming family in the South Okanagan, where trees are cut down and replanted every Read more