Blog

-

Do Tree Protection Bylaws really “protect” the urban forest since the introduction of new housing regulations and legislation?

Tree Protection bylaws for the urban forest are municipal. Each municipality is slightly different, but they are all affected by provincial legislation. Citizens believe that these bylaws protect the urban forest. The word “protection” is in the name, so it’s a fair assumption, but it requires a deeper look. Let’s use the City of Victoria’s Read more

-

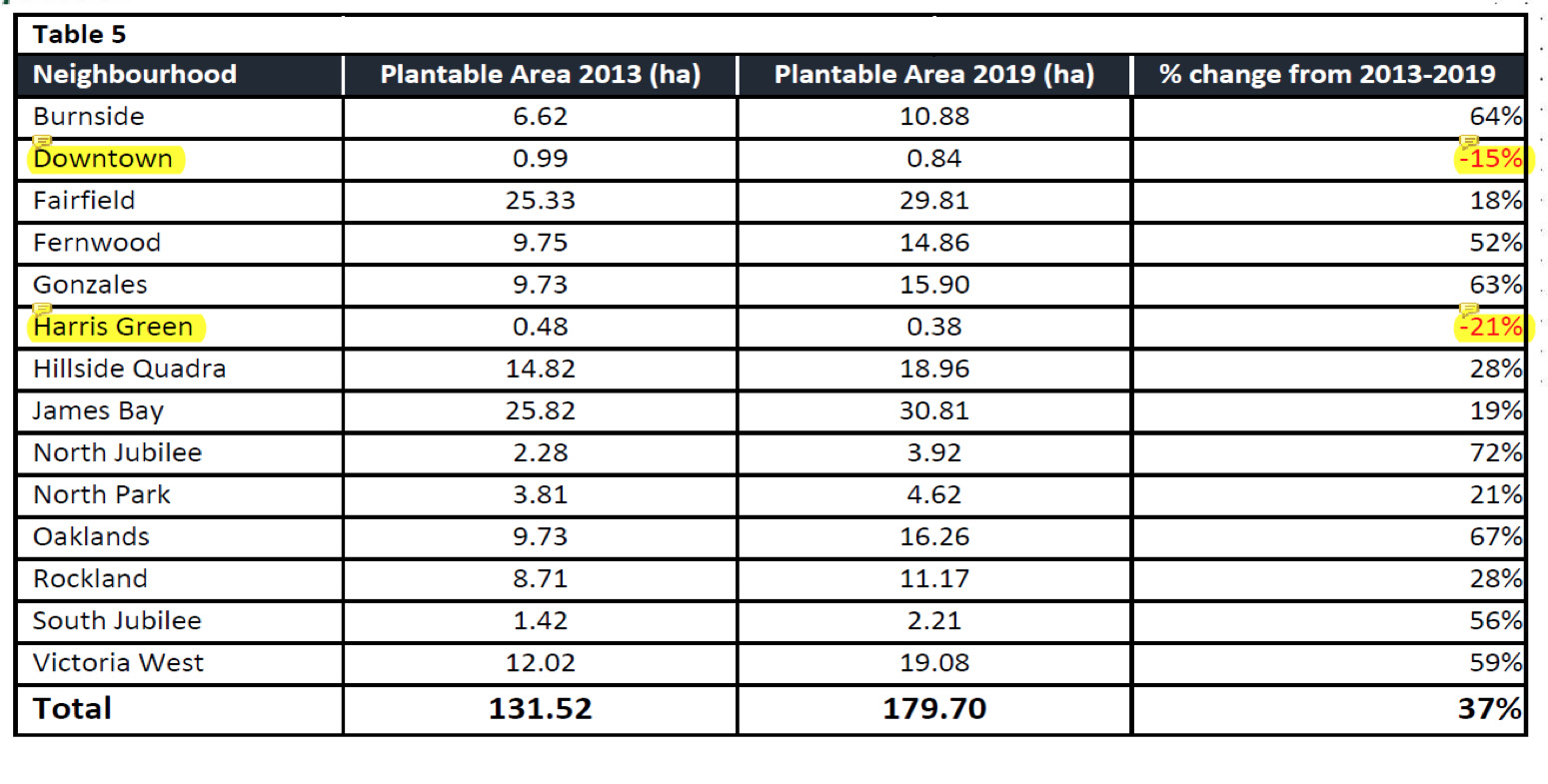

Why is Plantable Space an important metric

As a measurement, plantable space is the leading indicator of an sustainable urban forest, while overall tree canopy measurement is a lagging indicator. A loss of plantable space reduces the opportunity for canopy at the local level, meaning at the neighbourhood level. The benefits that the trees provide and protects the whole of a city for shade, stormwater and heat reduction through evaporation. Read more

-

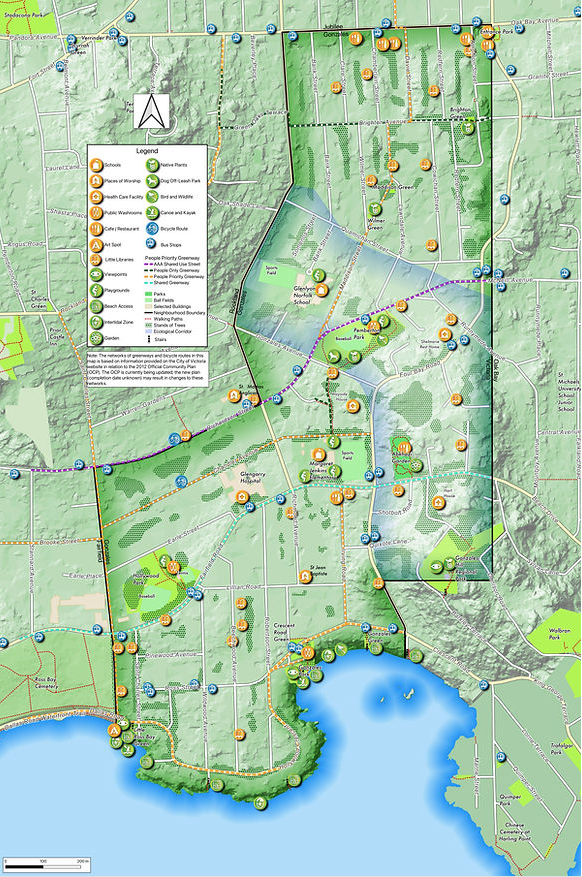

Gonzales Community Green Map

In 2018, the Gonzales Neighbourhood Association (GNA) initiated a community mapping exercise in cooperation with the University of Victoria – Geography Department. Seven years later, they are proud to announce that the Community Map is finished. The 2025 map includes a proposed migration corridor that links the ocean environment found at the Gonzales Observatory with the protected Read more

-

Urbanists vs. the Nature in My Backyards. District of Saanich – Special Council Meeting for Draft Quadra McKenzie Plan July 7th, 2025.

A Special Council Meeting was held at the District of Saanich’s July 7th meeting regarding the proposed Quadra McKenzie Plan (QMP). More than 100 people packed Saanich municipal hall. Each presenter had three minutes to provide input. The Quadra McKenzie plan, which has been in the works since 2023, will decide how a major chunk Read more

-

Remote Sensing: Garry Oak Species Detection Project

Squirrel for Mayor was at the Victoria International Airport on June 24, 2025 for the Remote Sensing: Garry Oak Species Detection Project with the Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society and Terra Remote Sensing to launch a Bell 206B3 Jet Ranger, equipped with a Phase One IXM-100 camera for aerial data acquisition to perform Garry oak species detection Read more

-

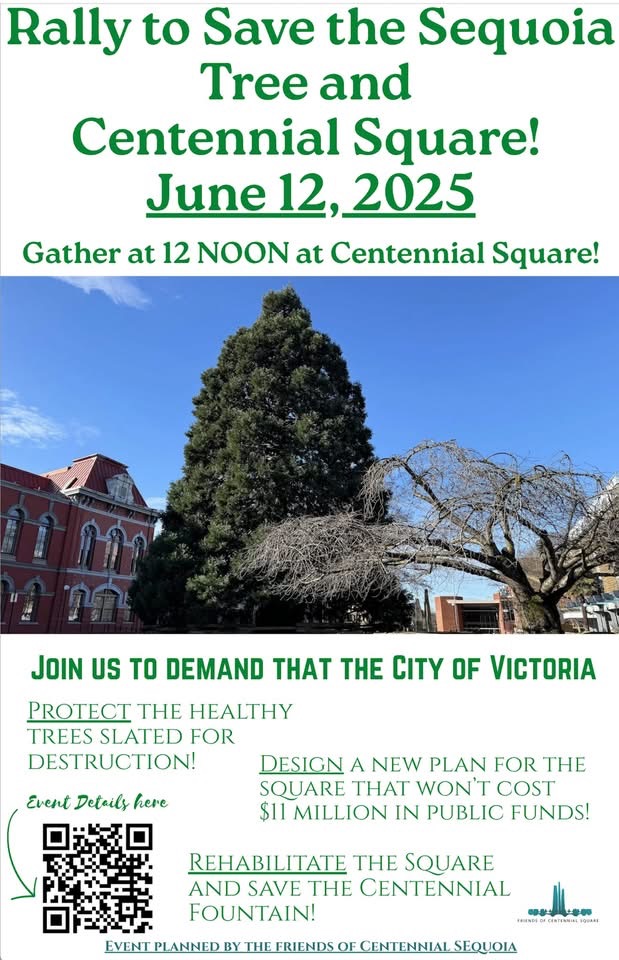

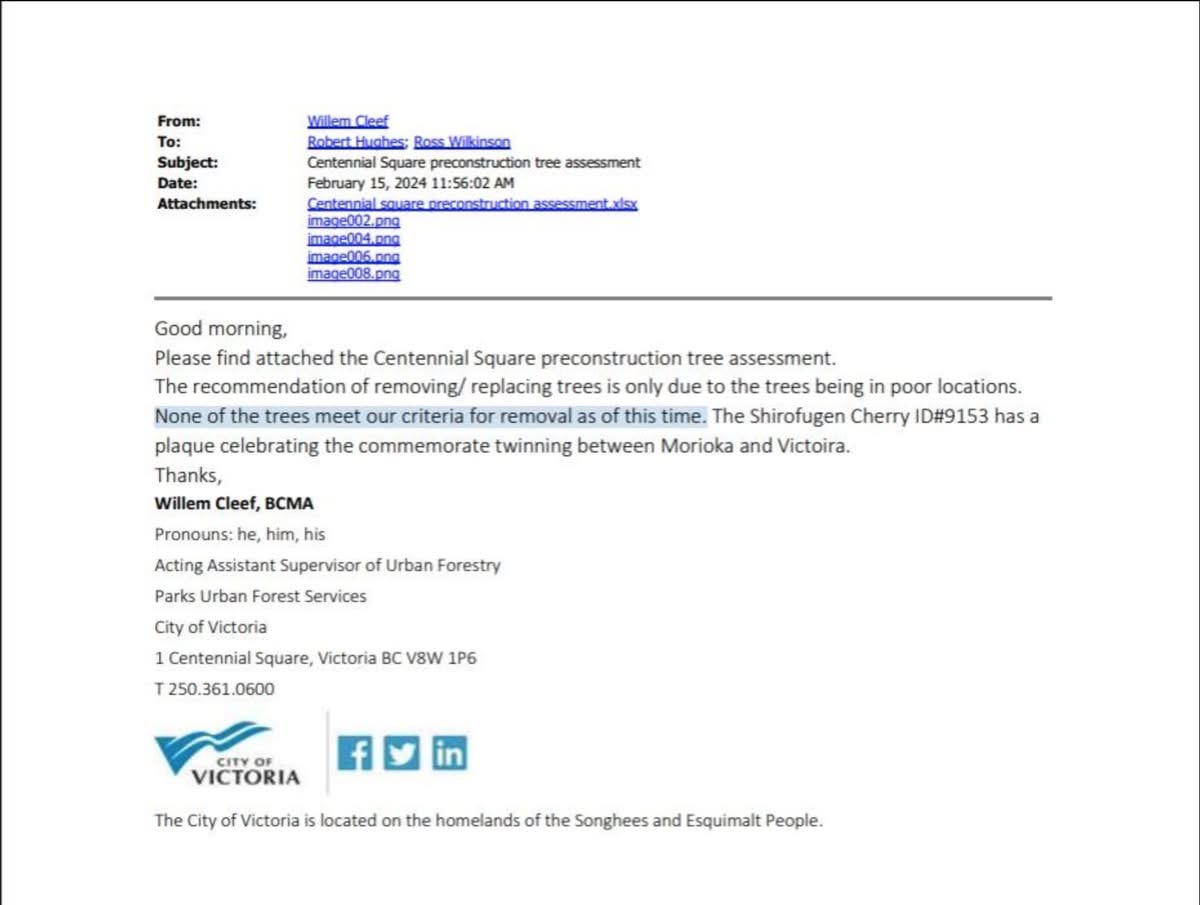

Index of documentation related to Centennial Square and the Sequoia

Originally posted at CRD WATCH In order to make information about Centennial Square and the Sequoia organized and easily accessible, CRDWatch.ca has made an index of documentation regarding Centennial Square and the Sequoia. The index is a stark challenge to the City of Victoria’s faulty narrative regarding the tree, which collapsed when faced with the analysis of a Read more

-

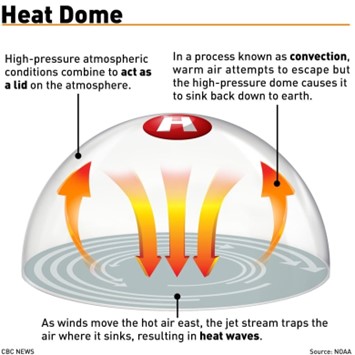

HEAT DOME ANNIVERSARY – CALL FOR LETTER SIGNING by June 23rd, 2025

CALL FOR LETTER SIGNING FROM: David Quigq (Sierra Club). Dr. Melissa Lem and I will be doing a press conference/media interviews on Tuesday June 24th at 11am in front of Eby’s office in Kits. That’s the morning we’ll submit the letter with signatories to the province. Please share this letter widely to organizations and individuals Read more